When I last posted here, Earth had just passed the Winter Solstice. Since then, I’ve made two forays into Greenville, the nearest town, about 30 miles distant. On my first trip, I celebrated Christmas with an Achor Earth Ways board member and his family (with attention to Covid precautions – no sitting around a group table for dinner this year). Then I returned to town for a few hectic days in early January. Among other errands, I needed to address various tasks related to the release of my new photo book, Living Every Season: A Mindful Year in the Maine Woods (stay tuned for the launch of online sales in a few weeks!).

January 11 was my final day in town. After rushing through a list that seemed to keep adding items as I neared its end, I was grateful to head back to the woods, looking forward to settling in and hunkering down. It was after dark when I arrived at Medawisla, a lodge operated by the Appalachian Mountain Club on Second Roach Pond. From there, it’s about three and a quarter miles, mostly over snowmobile trails, to my cabin on the shore of First Roach. Staff were preparing to open for cross-country skiers on Martin Luther King weekend, and the manager had graciously offered me a parking spot in a plowed lot. I checked in with her before hitting the trail. Wasn’t I spooked by the thought of traveling alone in the dark, she asked? No, I replied, I have a good headlamp and know the route well. Besides, for me, this is home.

I loaded up my gear sled. I didn’t want to know how much it weighed. I had no intention of heading out again before February, so I had plenty of supplies, including heavy items such as meat, fresh fruit and veggies, and liquids (lamp oil, cleaning supplies, milk, and, yes, a bit of wine). I also had a sizable pile of freshly-laundered clothing and assorted electronics. My guess is that the total approached 100 pounds. I strapped on my snowshoes, shrugged a daypack onto my back, buckled the sled’s harness around my waist, slipped my hands through the loops of my trekking poles, and set off. To my relief, I found that much of my route had been packed by snowmobiles, making the sled considerably easier to pull.

Along the way, I enjoyed a couple of wildlife encounters. I had hoped I might see a lynx that Medawisla’s manager spotted near a bridge over the Roach River, but I’ll have to keep looking on future trips. Farther along, I startled a grouse out of the bed it had hollowed in the snow. And as I approached my cabin, a pack of coyotes chorused in yips and yowls just to the west. Overhead, Orion, the hunter, shone brightly as he strode across the black sky.

I got a fire going in my woodstove, hauled water from the pump, and unpacked. And then, it seemed a primordial switch deep in my brain flipped, sending a signal to my mind and body that it was time to hibernate.

I was deep in the stillness of winter-dormant woods, more than a mile from the nearest fellow human, with nine hours of day and fifteen of night. I had no predetermined schedule, no life-or-death items on my “to-do” list.

I hadn’t fully realized how exhausted I was. Since the end of last May, when Covid lockdown restrictions eased, I had juggled many commitments: work as an off-the-grid Census enumerator, management of a hiker visitor center for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, completion of my photo book, multiple other writing assignments, and, finally, preparation for my winter at the cabin. Sleep often got squeezed out of my schedule.

What a blessing to have time for deep rest, to sleep as long as I need, to sit quietly in my rocker in front of the glowing fire. And yet, as I’ve rested, my mind and body have remained active – in ways very different from my usual life on the grid.

In the woods, regular physical activity is essential for survival. My only water for drinking and cooking, not to mention washing, is the water I pump by hand and carry in pails to my cabin. My only source of heat is wood that I carry from my shed, then split with an axe and sledgehammer into appropriate sizes for ignition. I don’t mind these tasks. They demand a level of mindfulness that turns them into a sort of working meditation. And they ensure that, even when I’m focusing on reading or writing, I get outside and exercise regularly. I’d estimate that I average 45 minutes a day on these basic activities of daily living. (In a future post, I’ll share more details of the mechanics of these chores.)

As for my mind, I’ve had time for intense contemplation that would generally be impossible in ordinary life. I’ve done a bit of reading, and I’ve spent some time online, especially around the inauguration. But off the grid, my Internet use is much more intentional than in town. There’s a limited supply of gasoline for the generator that charges the battery that powers my satellite dish. So I plan what I really need to do online, plug in the dish, and then try to be fairly efficient. I’m acutely aware that every frivolous YouTube video or random scroll through my Facebook newsfeed diminishes my remaining fuel supply.

My contemplation is not always easy. When doubts or fears or regrets come up, I can’t fall back on the endless supply of distractions offered in our high-tech society. I have no choice but to think things through. Though I’ve been blessed in countless ways, and known much joy, every life has its challenges. It’s taken me longer than I hoped to find a publisher for my book Heaven Beneath Our Feet, into which I’ve poured years of passion and labor. I still grieve the death of my mother – my dearest friend – who passed away seven years ago. But somehow, as I’ve wrestled with emotions I wished I weren’t feeling, the stillness of my surroundings has helped me to be gentler with myself. The woods and waters and mountains, the icy winds that sometimes roar around my little cabin, the swirling snowfalls that cocoon it, wordlessly whisper peace to my heart and mind. They seem to encourage me to reframe my shortcomings and disappointments as opportunities for future growth, rather than sources of crippling regret. Will I be able to hang on to this perspective when I reenter the busier world outside the woods? I’m not sure, but I’ll know I’ll try.

Now, after two weeks of hibernation, I feel my inner energy beginning to flow. I’m looking forward to being able to ski and snowshoe over the surface of First Roach Pond sometime soon. Overall, the winter has been relatively mild, but with colder temperatures this week, the ice has thickened. I stepped outside one night to hear the music of crystallizing water: rolling rumbles punctuated by sharp cracks, some loud enough to echo off the trees and hills along the shore.

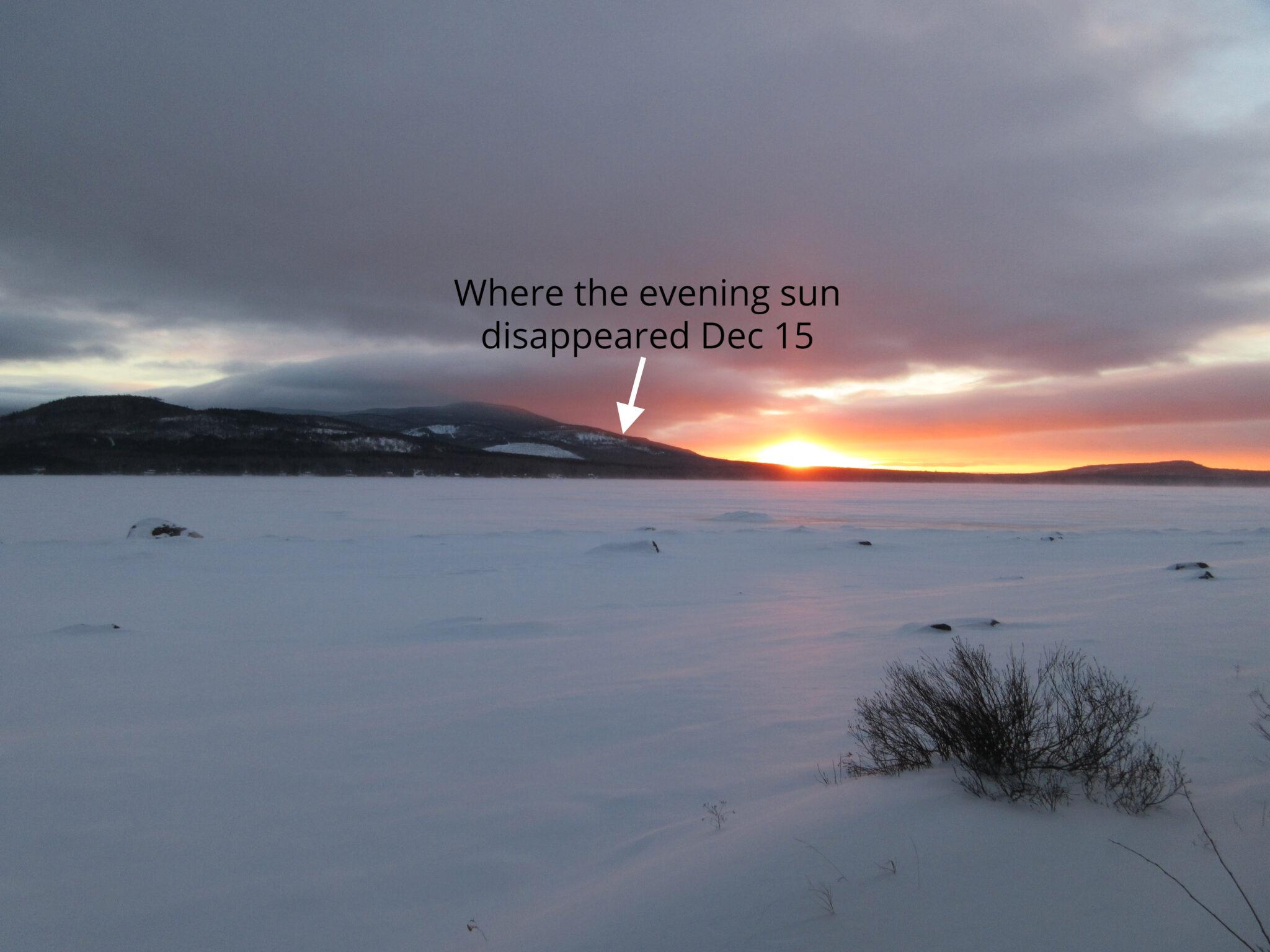

And the days are growing longer, meaning there will soon be enough light for wanderings farther afield. The sun sets a bit later, and a bit farther north, each evening. We’ve already gained 45 minutes of daylight since the Winter Solstice. I’m starting to think about trails I’ll want to explore. The year is moving forward, and I’m eager to start moving with it.