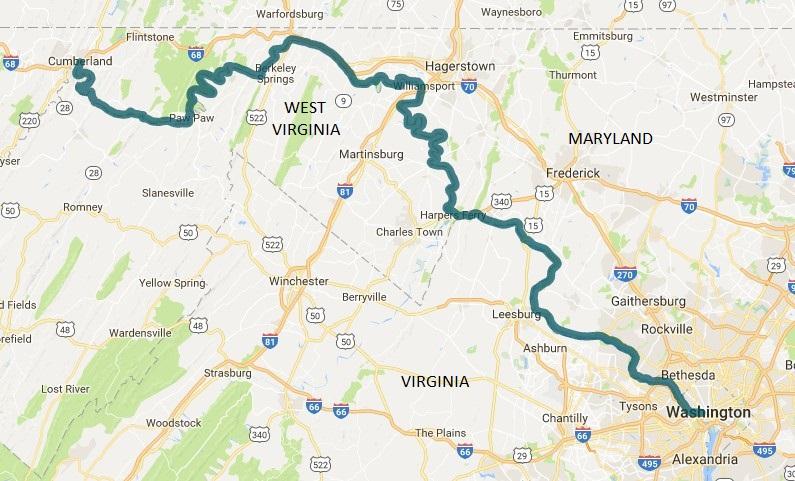

After my last post, on May 2, I walked five more days along the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal to reach its terminus in Cumberland, Maryland, a small city in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.

En route, I passed through the Paw Paw Tunnel, a notable feat of nineteenth-century engineering. Over the course of fourteen years (1836-1850), laborers blasted and chiseled their way through six tenths of a mile of solid rock – slow and dangerous work that allowed the canal to bypass a meandering stretch of the Potomac River known as the Paw Paw Bends.

The name “Paw Paw” refers to a small native tree that produces large edible fruit, up to six inches in length. In April, as I walked through woods near Washington, DC and Harpers Ferry, paw paw trees were in bloom, maroon flowers strung along their branches. I’d welcome the chance to try the fruit that will mature from the fertilized blossoms – it reportedly tastes like a cross between a banana and a mango. Maybe someday I’ll revisit this area when they’re ripe?

During my final few days on the trail, I saw and heard signs that many creatures were getting down to their primary business: producing offspring. The bird songs we enjoy as nature’s music have a serious purpose. They generally come from males who are inviting females to join them and/or warning other males to stay away. As I passed a wetland that lay between the canal and the Potomac River, I paused to witness the drama of male red-winged blackbirds arguing over territory. Red-wings proclaim ownership of their domains with a short song ending in a rapid trill that sounds like an electric buzzer. When one singer, perched on a cattail, was approached too closely by another bird, he took flight and gave chase, insisting that the intruder back off and respect his personal space.

Amphibian mating season continued in full swing. Amorous male frogs loudly advertised their interest in any and all ladies of the same species. Spring peepers – which I had heard even at the beginning of my journey, in mid-March – still sang their whooping chorus at night. At a particularly musical campsite, gray tree frogs added their slow trills to the peepers’ vocalizations. During daylight hours, I heard my first bullfrogs of the year, their booming “jug-o-rum” heralding the approach of summer.

Butterflies were gearing up for reproduction too. Male tiger swallowtails were “puddling,” gathering at moist spots on the ground to imbibe salt. Salt is a valuable commodity during mating, when a male can pass it along to a female partner to enhance survival of their fertilized eggs. (For more on this phenomenon, see naturalist Mary Holland’s post at https://naturallycuriouswithmaryholland.wordpress.com/2016/05/31/canadian-tiger-swallowtails-puddling/.)

On May 7, Achor Earth Ways board member Patti Moore met me when I arrived in Cumberland. Patti treated me to a crab cake lunch in celebration. It tasted wonderful after days of monotonous trail fare, limited to items such as peanut butter, tuna packets, granola bars, and dried fruit. (I had omitted my backpacking stove so I could carry extra electronics, including a laptop and a solar charger for my phone.)

Cumberland was not quite the end of my trek: one final segment remained. From its start in Washington, DC, to its end in Cumberland, the canal runs roughly parallel to the Potomac River for 184.5 miles. I had begun hiking the canal at mile 5, on the Maryland side of the Maryland/DC boundary line, and headed westward. On May 8, Patti and I returned to mile 5 and walked eastward into Washington, completing the final five miles of my journey together.

After entering the city, we were pleasantly surprised to find that the canal and river still offered a sense of wildness. We stopped for a snack at Fletcher’s Cove, where urban dwellers can fish for shad, bass, perch and catfish from the tree-lined riverbank, paddle in a rented canoe, or enjoy a birding expedition.

As we followed the canal deeper into Washington, the city did eventually assert itself. In the historic neighborhood of Georgetown, buildings crowded both sides of the canal. Even so, it seemed to provide a ribbon of habitat for non-human species. A friendly man with long gray hair stopped us – and anyone else who would listen – to point out a group of seven ducklings huddled in a narrow strip of grass at water’s edge.

After passing through Georgetown, the canal joins Rock Creek, which then flows three-tenths of a mile down to the Potomac River. There, Patti and I found Mile Marker 0, the endpoint of my journey.

A pair of Canada geese with their goslings served as our welcoming committee. Nearby, I spotted an interpretive sign that gave me a bit of hope for the future of the wild. The text explained that, for thousands of years, this was where herring migrating from the Atlantic Ocean entered Rock Creek to swim upstream to their ancestral spawning grounds. But human development along the stream – dams, fords, and sewer lines – blocked upstream access for the fish. Recently, engineers adapted these obstacles to allow fish passage. The “Herring Highway” is open once again, a wild vein running through the heart of an urban/suburban region.

I confess I was a bit disappointed when online research revealed that the story was more complex than the sign indicated. The engineers who performed the Rock Creek restoration did the work as legally required compensation; it was a counterbalance to environmental damage they caused during work on a bridge over the Potomac River. One step forward, one step back. Still, the Rock Creek herring run is an example of how we can choose to reintegrate wild nature into our lives, even in densely populated areas. And the herring have become a source of practical education for local schoolchildren, connecting city kids with the wild in a way that textbooks can’t.

I took my first steps on this journey March 10 at Cape Henlopen State Park on the Delaware coast and walked 86.5 miles to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. I hiked the 184.5 miles of the C & O Canal (well, excepting two and a half miles that were closed due to a washout). I stopped in Baltimore, Washington, and Harpers Ferry, meeting with people ranging from senators to a homeless poet. I sought – and found – the wild wherever I went, in both rural and urban settings. I talked with many people about the importance of our connection with nature, both for our own health and the health of the Earth. I learned far more than I taught. I was sustained by the love and support of friends: a few who walked with me in person, and many more who offered encouragement, wise counsel, or financial contributions from afar. I was blessed abundantly by unexpected kindness from strangers, in the form of food, shelter, rides, and help navigating unexpected obstacles along the trail. Along the way, I found time and space to explore my inner wild as well, learning more about hidden places in my own mind and heart.

It seems fitting that that my trek ended at Mile Marker 0, signifying not a finish but a start: the beginning of my onward journey.